I. Introduction

There is something inconsistent about crowdsourcing in the humanities. Crowdsourcing in the sector is employed mostly for the transcription or classification of data, tasks which are largely devoid of interpretation. However, humanities students in most disciplines are trained to do exactly this – to interpret and communicate information and opinion. Despite this, there have been some great successes, with the designers of humanities projects doing fantastic work in setting up websites employing the intelligent use of gamification, a quite maligned design technique (see, for example, the article on the class reading list with the concise title ‘Gamification is Bullshit’).

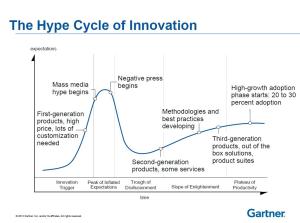

Put simply, gamification is the application of game design theory and techniques in non-game settings to engage users. The term ‘gamification’ emerged in 2008 to describe the increasingly widespread online use of game elements like leaderboards and badges, was quickly billed as an easy way to engage customers and increase sales, and was then just as quickly deemed a useless trend that should be consigned to the past.

The problem with the extensive recent coverage of gamification is that it largely ignores the fact that gamification was not ‘invented’ in 2008, that was just when the term was coined. Game design principles have been employed in other contexts for years. Take reward cards as an example (buy a certain amount of something to get one free), which appeared in the late 1800s. Zichermann and Cunningham point out that they rarely make economic sense for the consumer to change their behaviour, but they are successful because customers have a challenge, a reward, and can see their progress. Likewise, frequent flyer programmes don’t just reward airline customers with free trips, they also ‘level up’ with gold and platinum cards. So gamification as a concept is quite catchall – game design is quite broad – and it is likely that ideas currently classed as ‘gamification’ will be absorbed into good user-focused design.

At the moment, gamification seems somewhere around the nadir of the post-hype comedown that most innovations suffer. Because of this, digital humanists are reluctant to acknowledge the use of the design theory in their publications. Below I’ll briefly introduce gamification and give an example of its appearance in digital humanities crowdsourcing.

II. Gamification Online

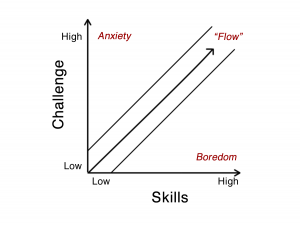

In recent years, as internet usage has pervaded almost every aspect of daily life, many organisations from online stores to social media have found themselves dependent on keeping people engaged with their website. It was quickly realised that the gaming industry had for decades been relying on exactly this – keeping people engaged, sitting in front of a computer. For this, game designers had developed the theory of ‘flow,’ the state which is produced in a game player by the correct balance of challenge and reward – if something is too hard, a player will get frustrated and quit, if something is too easy, they will quickly tire of it (this is why, for example, games are split into levels that get progressively harder).

Another, less mentioned element that is key to gamification is how it should build on the existing motivation of the user. Great examples of gamification are sites and apps that expand upon the existing motivation of the user. Yelp is a crowdsourced review site that allows people to gain status in the site’s community by becoming top commenters and having greater authority on the site. This works well because it builds upon the motivation to share reviews – the desire to have one’s opinions listened to and considered important. Nike+, is a fitness app that organises and simplifies users’ fitness goals and tracks their progress, collecting badges along the way like ‘Streak Week’ (that particular badge is for running every day for a week). This works well because it reinforces long-term motivation of improving fitness with short-term, easily reachable goals like levelling up to a new badge, keeping the user in a state of flow.

III. Gamification in Digital Humanities

So, returning to the opening inconsistency, how do good humanities crowdsourcing projects tailor their design around existing motivations and keep their users engaged?

The best example of gamification being used well in a crowdsourced humanities project is University College London’s Transcribe Bentham project. The challenge is huge: to transcribe 40,000 unpublished folios handwritten by Jeremy Bentham, many of which were written in increasingly bad handwriting and chaotic order as the philosopher aged and lost his sight. However, the designers of Transcribe Bentham have built a platform that has created a community of frequent contributors who, by logging in and transcribing in their spare time have completed around 40% of the task as of October 2014.

Transcribe Bentham incorporates leaderboards and badges, allowing transcribers to move up through the ranks from ‘apprentice’ to ‘scribe,’ and on up. As with Yelp, the gamification builds on the users’ pre-existing motivation (to explore previously unavailable writings by Bentham himself), and as with Nike+, the users have frequent, achievable goals and rewards (levelling up), keeping users in a state of flow. Although Stuart Dunn has validly pointed out that gamification has the potential to trivialise input, the application of its techniques can definitely work in this transcription context.

Bibliography & Further Reading

Bogost, Ian. ‘Gamification is Bullshit: My position statement at the Wharton Gamification Symposium,’ blog post 2011. Available from http://bogost.com/blog/gamification_is_bullshit/

Causer, Tim; Terras, Melissa.’”‘Many hands make light work. Many hands together make merry work”: Transcribe Bentham and Crowdsourcing Manuscript Collections’ in Ridge, Mia, Crowdsourcing our Cultural Heritage, Ashgate, 2014. Available as a pdf file from http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1393567/

Clancy, Heather. ‘Looks Like That Whole Gamification Thing is Over,’ in Fortune, June 6, 2014 http://fortune.com/2014/06/06/looks-like-that-whole-gamification-thing-is-over/

Deterding, Sebastian; Dan Dixon; Rilla Khaled; Lennart Nacke. ‘From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining “Gamification,”’ in Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments. ACM, 2011, 9-15.

Dunn, Stuart. Crowdsourcing Scoping Report,London, 2012. Available from http://crowds.cerch.kcl.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Crowdsourcing-connected-communities.pdf

Holley, Rose. “Crowdsourcing: How and Why Should Libraries Do It?” D-Lib Magazine 16.3/4 (2010)

Cunningham, Christopher; Zichermann, Gabe. Gamification by Design. 2011, 5-13. Available as a free ebook here http://it-ebooks.info/book/570/

Image Sources:

Gartner Hype Cycle of Innovation: http://romainiacs.com/2013/08/26/emerging-technologies-hype-cycle-for-2013-released/

Flow diagram: http://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/ZacharyFitzWalter/20120426/169287/Gamification_Thoughts_on_definition_and_design.php

Interesting article Will. I just watched the most recent episode of “South Park” entitled “Freemium isn’t Free” which is all about free games with micro-transactions, targeting in particular “The Simpsons All Tapped Out”. It demonstrated how games with a lagging “Flow” can be accelerated with in-game payments to make them more enjoyable. “South Park” made the point that these games are trained at people with addictive personalities the same way drinks and cigarette companies are, even crowd-sourcing, the figure of the “super-user” clearly having addictive personality traits.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freemium_Isn't_Free

LikeLike